Diocese of Artsakh of the Armenian Apostolic Church

The Gandzasar Monastery belongs to the Diocese of Artsakh of the Armenian Apostolic Church (Armenian: Հայ Առաքելական Եկեղեցի). The Diocese of Artsakh is the Church’s easternmost historical division.

In 301 AD,Armenia became the world’s first Christian kingdom that officially proclaimed Christianity as state religion; the Byzantine Empire would wait until 361 AD to do so. In 301 AD, St. Gregory the Enlightener converted to Christianity Trdat III, King of Armenia (Tiridates III in Greek and Latin sources), and members of his court. The Church teaches that St. Gregory was imprisoned by Trdat III and put, for 13 years, in an underground pit called Khor Virap (Armenian:

Խոր Վիրաբ). But St. Gregory, who had miraculous powers, healed the King of an incurable disease, and Trdat’s conversion followed immediately. [1]

The Armenian Apostolic Church has been in existence since the days of the apostles and therefore is one of the oldest Christian churches. The Church teaches that the Christian faith was first preached in Armenia by two Apostles of Jesus Christ: St. Bartholomew and St. Jude (St. Thaddeus).

The Armenian Apostolic Church is also the world’s oldest national Christian church. In 451 AD, the Church rejected the decisions of the Council of Chalcedon, and in 554, during the second Council of Dvin, it officially severed ties with the Universal Church. Since then, the Church has intentionally confined its main activities to Armenian communities, both in Armenia and its Diaspora.

Christianity was strengthened in Armenia by the translation of the Bible into Armenian by St. Mesrob Mashtots, the Armenian theologian and scholar who invented the Armenian and Georgian alphabets, in around 406 AD, and established the first Armenian school on the territory of the Nagorno Karabakh Republic (Amaras Monastery) in around 410 AD. The Armenian Bible has 48 books in the Old Testament. The New Testament is the same as in the Roman Catholic and Protestant Bibles.

Christianity in Armenia’s Eastern Provinces

In contrast to most other dioceses of the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Diocese of Artsakh has a centuries-old tradition of autonomy within the Church. This is due to the fact that Artsakh and the neighboring province of Utik, known together in Armenian geographical nomenclature as the Eastern Prefectures of Armenia (Armenian: Կողմանք Արևելից Հայոց), had a longer history of self-rule than the country’s most other provinces. [2]

The legend states that official Christianity in Artsakh began with the conversion of Urnair (Armenian:

Ուռնայր

), a local Armenian chieftain, in the fourth century, by none other than the Armenian evangelizer St. Gregory the Enlightener, who traveled to Artsakh after baptizing the Armenian king Trdat III in 301 AD. As suggested by Movses Kaghankatvatsi, the native Armenian historian of Artsakh and Utik and author of the “History of the Land ofAghvank” (Armenian:

Պատմություն Աղվանից Աշխարհի), St. Gregory named a certain Thovmas of Satala as bishop shortly thereafter. [3]

In about 330 AD, the grandson of St. Gregory, St. Grigoris—the appointed ecumenical head of Armenia’s eastern provinces—was designated bishop for Armenia’s Kingdom of Aghvank, which included Artsakh. St. Grigoris was killed by the pagans, in 338 AD, when teaching Gospel in the Land of the Mazkuts (or Massagetae, tribes in the present-dayRepublic ofDagestan, in Russia ’sNorthern Caucasus). St. Grigoris’ remains were brought to Artsakh by his disciples and buried inside a mausoleum located underneath the Amaras Monastery—the oldest dated monument in Nagorno Karabakh. Amaras was established by St. Gregory and completed by St. Grigoris.

According to tradition, the Amaras Monastery housed the first-ever school in Armenia where teaching was based on the Armenian alphabet, invented around 406 AD by St. Mesrob Mashtots. [4]

St. Mesrob was very active in preaching Gospel in Artsakh and Utik. Movses Kaghankatvatsi’s “History…” dedicates four separate chapters to St. Mesrob’s mission, referring to him as “enlightener,” “evangelizer” and “saint” (chapters 27, 28 and 29 of Book One, and chapter 3 of Book Two of the History of the Land of Aghvank). Overall, St. Mesrob made three trips to Armenia’s east where he toured not only Artsakh and Utik but also pagan territories to the north of the River Kura, ultimately reaching the foothills of the Greater Caucasus.

Rise of the Holy See of Gandzasar

The Gandzasar Monastery’s transformation into the center of Christianity in the eastern provinces of Armenia was connected to the rise of Artsakh’s largest Principality of Khachen (Armenian:

Խաչենի Իշխանություն) in the 13th century, under its famous ruler—Grand Prince Hasan Jalal Vahtangian.

From the late 14th century to 1836, the Gandzasar Monastery housed the easternmost subdivision of the Armenian Apostolic Church known as the Holy See of Gandzasar. Gandzasar administered parishes not only in Artsakh and Utik but also in all the lands that lied in the triangle formed by eastern border of Armenia along the River Kura, the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus Mountains.

Diocese of Artsakh in the Nineteenth Century

In 1805, Artsakh and Utik were conquered by the armies of the Russian Tsar, from Persia , and made part of the Russian Empire. In 1815, under the pressure from the Mother See of Saint Echmiadzin, Russians lowered the status of the Holy See of Gandzasar to that of a Metropolitanate. It was not until 1836, however, when the actual Diocese of Artsakh was organized, with the Mother See (Katholicosate of Echmiadzin) regaining direct authority over all parishes of the former Holy See of Gandzasar.

Beginning from 1857, the Diocese of Artsakh was split into two sub-dioceses: the Diocese of Karabakh and Diocese of Shamakhi. A separate Vicariate of Gandzak, subordinated to the Church’s consistory of Tiflis (Georgia ), took care of Armenian parishes of Utik and Gardman, lands found south of the town of Gandzak (Gandja, in modern Azerbaijan).

In 1914, the Diocese of Karabakh had 222 functioning churches and monasteries, with 188 clergymen, and 206 thousand parishioners living in 224 Armenian settlements.

Diocese of Artsakh after the Russian Revolution

After the Russian Revolution Bolsheviks severed Nagorno Karabakh from Armenia and gave it to Soviet Azerbaijan, despite the vociferous protests of its autochthonous Armenian majority. As a result, Armenian Christianity in the province fell under the double yoke of ethnic persecution by Azerbaijani nationalists and religious pressure by the USSR ’s atheist authorities. All Armenian churches in the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Province were closed down and subjected to intentional neglect. Ultimately, many of them fell into disrepair or were wrecked by dynamite-armed emissaries from Baku. The Diocese of Karabakh was liquidated as early as in 1930, with Nagorno Karabakh’s Armenian priests killed on the spot or exiled toSiberia.

Following Communist and Azerbaijani nationalist repressions, the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Province became the only Soviet national territorial unit that did not have a single functioning church despite the fact that over 90 percent of its population was Christian. In contrast, the province’s tiny but privileged Muslim (“Azerbaijani”) minority had at its disposal two fully-functioning mosques in the town of Shushi, and one large mosque in the nearby town of Agdam.

Some Armenian clergymen from Nagorno Karabakh, however, survived the persecution and even advanced to high positions in the hierarchy of the Armenian Apostolic Church. The most prominent of them was, undoubtedly, Katholicos Garegin I Hovsepian (1867-1952). Garegin Hovsepian was born in the town of Maghavuz, in Nagorno Karabakh’s northern county of Jraberd. He personally led Armenian troops during the battle of Sardarapat (May 25, 1918), against the invading Ottoman army, and later gained prominence as an art historian. After serving in Armenian Diaspora communities for years, Garegin Hovsepian was elected Katholicos of the Holy See of Cilicia, becoming the second most important hierarch of the Armenian Apostolic Church at the time.

Diocese of Artsakh Today

The Karabakh Liberation Movement that began in 1988, three years before the official dissolution of the USSR, had as one of its goals the attainment of religious freedom, revival of Christian life and re-consecration of ancient Armenian churches and monasteries in Nagorno Karabakh. In 1989, under pressure from Nagorno Karabakh, Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora, the Soviet authorities in Moscow made a decision to make the monasteries of Gandzasar and Amaras available for religious practice. The Armenian Apostolic Church received an opportunity to revive its Diocese of Artsakh, and sent priests to Nagorno Karabakh.

In 1991, the Diocese of Artsakh established in Yerevan the theological center “Gandzasar” devoted to the development of religious thought and education of the public. The center has published more than 60 books; it also has a radio station that has been introducing the public to worship, church, and the Christian Faith, and creating the bonds of love and community that best captures the essence of being Christian.

Beginning from 1997, the Diocese of Artsakh has supervised the teaching of “Lord’s Word” and “History of Religion” courses in secondary schools of the Nagorno Karabakh Republic.

The Diocese of Artsakh is headquartered at the Gandzasar Monastery and operates mainly from offices in the City of Shushi, not far from the Cathedral of the Holy Savior “Ghazanchetsots.” Shushi is the second largest settlement of the Nagorno Karabakh Republic and the region’s traditional center of culture. The Diocese is chaired by an archbishop of the Armenian Apostolic Church, and has under its supervision more than 30 churches and monasteries in the Nagorno Karabakh Republic. Besides Gandzasar, these include the renowned masterpieces of Armenian architecture: Amaras Monastery (4th century), Tzitzernavank Monastery (4th-6th centuries), Dadivank Monastery (1214-1237), Gtichavank Monastery (1241-1246), Cathedral of the Holy Savior “Ghazanchetsots” in Shushi (1868-1888), and Church of the Holy Mother of God “Kananch Zham” (1848-1850).

Baku’s Reaction to the Revival of Christianity in Nagorno Karabakh

Azerbaijan’s reaction to the revival of Christianity in Nagorno Karabakh was harsh and uncompromising. In order to punish Armenians for aspiring to religious freedom, official Baku used its military that was supported by Turkish advisors, Russian and Ukrainian mercenaries, Afghan mujahideen fighters and Muslim terrorists from Chechnya and elsewhere.

The Gandzasar Monastery suffered from the 1991-1994 war. Periodical aerial and artillery attacks on the monastery by Azerbaijanis were aimed at destroying Gandzasar as an emblem of Armenian spiritual life. The most direct of the attacks took place on January 20, 1993, when an air-to-earth rocket launched from an Azerbaijani MIG-21 air-jet pulverized one of ancillary buildings. Shrapnel left holes and scars on the lower portion of the northern wall of the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist. It is perhaps symbolic that it was near Gandzasar where first large regiments of Azerbaijani Army were rounded up and destroyed by the Nagorno Karabakh self-defense units, in 1992.

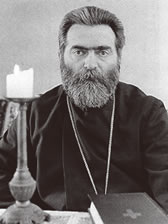

Archbishop Pargev Martirosyan, Head of the Diocese of Artsakh

His Beatitude Archbishop Pargev Martirosyan, Head of the Diocese of Artsakh of the Armenian Apostolic Church, in his office at the Gandzasar Monastery

Beginning from 1989, the Diocese of Artsakh has been headed by His Beatitude Archbishop Pargev Martirosyan.

Archbishop Pargev was born Gurgen Martirosyan, in the city of Sumgait, Soviet Azerbaijan. He hails from an Armenian family with roots in Northern Artsakh’s renowned town of Chardakhly. Located in Armenia’s historical county of Gardman, Chardakhly is known primarily for giving Armenians top military talent, including Hovhannes Baghramian (Marshal of the Soviet Union) and Hamazasp Babajanian (Marshal of the USSR ’s Armored Forces).

In 1971, Pargev Martirosyan graduated from a Yerevan mathematical school; in 1971-1976 he studied at the Yerevan Polytechnic University and V. Brusov Institute for Foreign Languages. In 1980, he was admitted to the Echmiadzin Seminary, and in 1983, after completing training at theological college, was ordained a deacon. After his graduation from the Seminary in 1984, Father Pargev assumed a post at the Mother See’s Treasury (Gandzasaran). In 1985, he assumed monastic orders and was sent to study at the Leningrad Theological Academy, in Russia.

In 1986, Father Pargev returned to Armenia and, after his consecration as archimandrite (called vardapet, Armenian: վարդապետ), was appointed as chief tutor of the Echmiadzin Seminary. In 1987, Father Pargev earned his doctoral degree in theology from the Leningrad Theological Academy. In the same year, he was appointed as Prior of the St. Echmiadzin’s historical Temple of St. Hripsimeh (built in 618 AD).

In November 1988, Father Pargev was bestowed upon the rank of Bishop. In June 1999, Bishop Pargev was promoted to the rank of the Archbishop of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Archbishop Pargev Martirosyan is the author of three books and numerous articles.

Archbishop Pargev Martirosyan is well known to international human rights activists. One of them is the Baroness Caroline Cox of Queensbury, a cross-bench member of the British House of Lords, and a world-renowned campaigner for many global humanitarian causes. Caroline Cox has been a champion of Nagorno Karabakh’s quest for freedom, independence and Christian revival, beginning from 1991. Here is how Archbishop Pargev Martirosyan is depicted in her book Cox's Book of Modern Saints and Martyrs published in 2006 in London, UK. Baroness Cox writes:

“During my second visit [to Nagorno Karabakh — aut.] in January 1992, I was in Stepanakert when Bishop’s Martirosyan’s house received a direct hit from a large bomb. He had been in bed (the only place, in those bitter days, where anyone could be warm, with temperatures at minus 20, and no electricity to give any heat or light). But as soon as the shelling began, he immediately got up to pray. Within one minute, the bomb hit his house – and a large concrete slab fell directly onto the bed where he had been sleeping. There was a case of a man whose life was literally saved by prayer! Bishop Pargev Martirosyan, primate of the Artsakh Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church, is a man of considerable intellect, substance and humanity, as well a man of faith. … When I visited the bishop in the ruins of his home, I asked if he would like to give a message to the rest of the world or to fellow Christians. He replied: “Our nation has again begun to find its faith [after 70 years of Soviet communism] and is praying in churches, in cellars, and on the field of battle, defending its life and the life of those who are near and dear. It is not only the perpetrators of crime and evil who commit sin, but also those who stand by—seeing and knowing—but who do not condemn it or try to avert it. Blessed as peacemakers for they will be called sons of God. We do not hate—we believe in God. If we want God’s victory, we must love. Even if there are demonic forces at work, not only in this conflict, but in other parts of the world, we must still love—we must always love. (Source: Butcher, Catherine. Cox's Book of Modern Saints and Martyrs. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006, pp. 100-101)

Father Ter-Hovhannes Hovannisyan

The Gandzasar Monastery is under the supervision of Rev. Ter-Hovhannes Hovannisyan, Prior of the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist and Father Superior of the Gandzasar Monastery. Father Ter-Hovhannes, a native of Nagorno Karabakh, was born in the historical town of Vank that lies beneath the Gandzasar Monastery. He actively participated in the historic defense of the monastery during the war for independence. Father Hovhannes is assisted by Father Ter-Grigoris.

— APPENDIX —

Armenia’s Patriarchs of Aghvank and the Holy See of Gandzasar

- Abas (Armenian: Աբաս, 551-595)

- Viro (Armenian: Վիրո, 595-629)

- Zakaria (Armenian: Զաքարիա, 629-644)

- Hovhannes (Armenian: Հովհաննես, 644-671)

- Uhtanes (Armenian: Ուխտանես, 671-683)

- Yeghiazar (Armenian: Եղիազար, 683-689)

- Nerses (Armenian: Ներսես, 689-706)

- Simeon (Armenian: Սիմեոն, 706-707)

- Mikael (Armenian: Միքաել, 707-744)

- Anastas (Armenian: Անաստաս, 744-748)

- Hovsep (Armenian: Հովսեփ, 748-765)

- Davit (Armenian: Դավիթ, 765-769)

- Davit (Armenian: Դավիթ, 769-778)

- Matte (Armenian: Մատթե, 778-779)

- Movses (Armenian: Մովսես, 779-781)

- Aharon (Armenian: Ահարոն, 781-784)

- Soghomon (Armenian: Սողոմոն, 784)

- Teodoros (Armenian: Թեոդորոս, 784-788)

- Soghomon (Armenian: Սողոմոն 788-789)

- Hovhannes (Armenian: Հովհաննես, 799-824)

- Movses (Armenian: Մովսես, 824)

- Davit (Armenian: Դավիթ, 824-852)

- Hovsep (Armenian: Հովսեփ, 852-877)

- Samuel (Armenian: Սամուել, 877-894)

- Hovnan (Armenian: Հովնան, 894-902)

- Simeon (Armenian: Սիմեոն, 902-923)

- Davit (Armenian: Դավիթ, 923-929)

- Sahak (Armenian: Սահակ, 929-947)

- Gagik (Armenian: Գագիկ, 947-958)

- Davit (Armenian: Դավիթ, 958-965)

- Davit (Armenian: Դավիթ, 965-971)

- Petros (Armenian: Պետրոս, 971-987)

- Movses (Armenian: Մովսես, 987-993)

- Markos, Hovsep, Markos, Stephanos (Armenian: Մարկոս, Հովսեփ, Մարկոս, from 993 to 1079)

- Hovhannes (Armenian: Հովհաննես, 1079-1121)

- Stephanos (Armenian: Ստեփանոս, 1129-1131)

- Grigor (Armenian: Գրիգոր, c.1139)

- Bejgen (Armenian: Բեժգեն, c.1140)

- Nerses (Armenian: Ներսես, 1149-1155)

- Stephanos (Armenian: Ստեփանոս, 1155-1195)

- Hovhannes (Armenian: Հովհաննես, 1195-1235)

- Nerses (Armenian: Ներսես, 1235-1262)

- Stephanos (Armenian: Ստեփանոս, 1262-1323)

- Sukias and Petros (Armenian: Սուքիաս, Պետրոս, c.1323-1331)

- Zakaria (Armenian: Զաքարիա, c.1331)

- Davit (Armenian: Դավիթ)

- Karapet (Armenian: Կարապետ, 1402-1420)

- Hovhannes (Armenian: Հովհաննես, c.1426-1428)

- Matteos (Armenian: Մաթեոս, c.1434)

- Atanas, Grigor and Hovhannes (Armenian: Աթանաս, Գրիգոր, Հովհաննես, 1441-1470)

- Azaria (Armenian: Ազարիա)

- Tovmas (Armenian: Թովմաս, c.1471)

- Aristakes (Armenian: Արիստակես)

- Stephanos (Armenian: Ստեփանոս, c.1476)

- Nerses (Armenian: Ներսես, c.1478)

- Shmavon (Armenian: Շմավոն, c.1481)

- Arakel (Armenian: Առաքել, 1481-1497)

- Matteos (Armenian: Մաթեոս, c.1488)

- Aristakes (Armenian: Արիստակես, 1515- c.1516)

- Sargis (Armenian: Սարգիս, c.1554)

- Grigor (Armenian: Գրիգոր, c.1559-1574)

- Petros (Armenian: Պետրոս, 1571)

- Davit (Armenian: Դավիթ, c. 1573)

- Philippos Tumetsi (Armenian: Փիլիփոս Տումեցի, reigned for one year)

- Hovhannes (Armenian: Հովհաննես, 1574-1584)

- Davit (Armenian: Դավիթ, c. 1584)

- Anastas (Armenian: Անաստաս, c.1585)

- Shmavon (Armenian: Շմավոն, 1586-1611)

- Aristakes Kolataketsi (Armenian: Արիստակես Քոլատակեցի, c.1588)

- Melikset Arashetsi (Armenian: Մելիքսեթ Արաշեցի, c.1593)

- Simeon (Armenian: Սիմեոն, c.1616)

- Petros Khandzketsi (Armenian: Պետրոս Խանձկեցի,1653-1675)

- Yeremia Hasan-Jalalian (Armenian: Երեմիա Հասան-Ջալալյան, 1676-1700)

- Yesai Hasan-Jalalian (Armenian: Եսայի Հասան-Ջալալյան, 1702-1728)

- Hovhannes Gandzasaretsi (Armenian: Հովհաննես Գանձասարեցի, 1763-1786)

- Sargis Gandzasaretsi (Armenian: Սարգիս Գանձասարեցի, 1810-1828)